Chicago Made: Meet The People

Meet The People: Alex Diamond Kwame Amoaku Nina Escobedo Steykine Wills |

TV + Film Industry Profile

Alex Diamond learns from Chicago P.D. work for filmmaking future

By Matt Simonette

Assistant Director Alex Diamond jokes that his professional abbreviation, “A.D.,” should really stand for “Anxious Director.”

“We always have to think of what could go wrong, and what could be an issue,” explained Diamond, a graduate of Columbia College and a veteran of several local independent productions. A resident of Chicago’s West Side, he is currently working as an assistant director on the longtime NBC drama Chicago P.D.

“Let’s say we’re filming outside a neighborhood house,” he added. “I have to make sure that all the houses are clear and that no one pops out [their door]. I have to think of everything that happens in there. I like to think that my vivid imagination helps me think of all the possibilities that can happen.”

Diamond describes himself as a “people person.” “That’s one of my favorite things and is a big part of film. You meet so many different types of personalities and you have to find a way to work together as a huge team.”

Diamond is a native of suburban Northbrook and jumped at the chance to work on a studio production.

“I thought that I’d really like to see what the studio life is all about,” Diamond recalled. “I’d really only been working on low-budget indie things, and a Lifetime movie and a BET movie. I wanted to see how a big television show ran.”

His first day working as a production assistant on Chicago P.D. was a “stunt day,” he added. “So I couldn’t say no.”

After working on the program for two seasons, he was asked to come on board full-time. Diamond said it helped that he was well-acclimated for the pace of a major production even before he left Columbia.

“I had a pretty good understanding and a pretty good feel for how a set ran,” he explained. “Then, after about three years [working on Chicago P.D.], my vision just sharpened and my focus got more clear. Now I really understand what 15 minutes on a film set means.”

Diamond is confident that his experience will help him when he is running his own productions one day.

“I’m seeing this flow throughout the day, and I think that is what is going to help me be a creative director—the one behind the monitors giving the actors direction,” he explained.

When not working on Chicago P.D., Diamond has been developing a “proof of concept” short film called Dopamine Dreams he hopes can be expanded into a feature or a television series.

The film is about “a naive drug dealer who meets a dark stranger at a party. We later find out this stranger is a drug kingpin for the underground music scene.”

Diamond has been working on Dopamine Dreams “since before college. It is ready to be green-lit and [begin] pre-production. This project…is actually what I have been pursuing my whole career and what ultimately made me change my life path and go to film school.”

He encouraged anyone seeking to break into film and television production locally to network and talk to people. “There’s a lot of social-network pages and communities that will allow you to volunteer on a film set. I [once] volunteered as a second A.D. on a short film, and a script supervisor suggested me to another company. For that, I made $800 in one day. At 24 years old, that was amazing at the time. It goes to show that there is no bridge you should ever burn [and you must] make sure you’re working the hardest you can.”

TV + Film Industry Profile

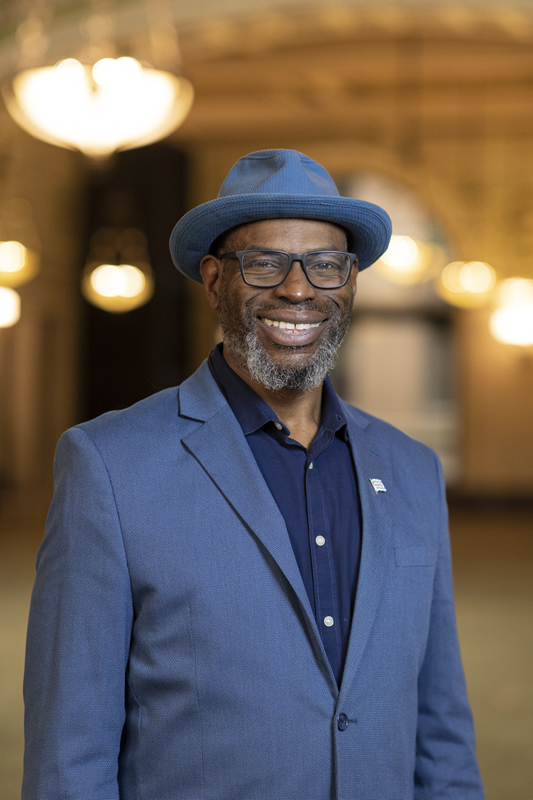

Kwame Amoaku: Chicago Made brings film and TV production opportunities to residents

By Matt Simonette

Chicago is continuing to boom as a center for film and television production. Last summer alone, some 15 productions added nearly $700 million to the city’s local economy. This was due to filmmakers, studios, and networks taking advantage of tax incentives making it cost-effective to shoot in the area.

But with the uptick in productions, there is also an uptick in demand for skilled workers. So Chicago Made, a workforce development initiative launched in 2021, has been linking Chicagoans to many of those positions.

“We’re specifically targeting groups of people that have skill-sets already in place that make them viable for the workforce in the film-production community,” said Kwame Amoaku, director of the Chicago Film Office at the Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE).

25 individuals were selected across 12 disciplines for the first cohort of workers. The program received about 500 applications.

“We’ve been looking for people between the ages of 25-50 who have skill sets in the trades that lend themselves to working in production,” added Amoaku, who suggested that persons with experience in carpentry, student film crew work or hair styling, among other fields, might benefit from Chicago Made.

“We’re looking for people who might have that experience who are missing the interpersonal connections that lead to employment in the film industry,” said Amoaku. “We have that deficit in the work force and we’re looking to fill that the fastest way possible, and we thought that using the talent that was already here in the city that lent itself to film production would be the fastest route to do that.”

Chicago Made is also geared towards reframing the public image of film and television production as an economic driver benefitting residents and neighborhoods, not a means for usurpers from Los Angeles or New York to “swoop in” and inconvenience locals with closed streets and lost parking spaces.

“We want people to understand that [many film crews] are blue collar workers,” added Amoaku. “These are neighbors and residents of the city of Chicago. Some of these jobs have been transformative in terms of diversity—our diversity numbers are much higher than in some other areas of the country.”

The State of Illinois administers a 30% rebate on money productions spend in the state; filmmakers can increase that rebate even more significantly if they work at hiring a diverse crew.

“It’s huge for these companies, especially in episodic television, where—as opposed to a movie, where you get one tax credit for the movie—you get a tax credit for every episode,” Amoaku explained. “So, for shows like the Chicago [Fire, P.D., etc.], shows where you do 22 or 23 episodes a year, it’s extremely beneficial for them and it’s why so many have taken up residence in the city.”

Amoaku was pleased that the local industry rebounded quickly after production shutdowns all across the industry that came early in the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We met with industry stakeholders and the Department of Public Health and came up with COVID guidelines that allowed film production to continue to operate as an essential economic industry,” he explained, adding that Chicago was one of the first cities to resume issuing film permits in June 2020. “It kind of showed the world that we were ‘open for business’ during this time.”

Beyond marketing Chicago as a viable film location and connecting locals with productions, another goal for the Chicago Film Office is bringing film screenings to neighborhoods throughout the city, Amoaku said.

“There used to be a lot of cinema houses where people could go and look at films in their neighborhoods,” he added. “A lot of that doesn’t exist anymore.”

In partnership with some of their partners, like the Park District and the Chicago Public Library, he hopes to do screenings to bring back cinema to those neighborhoods.

TV + Film Industry Profile

Nina Escobedo: Bringing a passion for costumes to Chicago’s TV and film industry

By Matt Simonette

Nina Escobedo credits her grandmother for sparking the childhood interests that ultimately led to her becoming a professional costumer working in Chicago.

“My grandmother taught me to sew at the age of four,” recalled Escobedo. “It started with buttons and embroidery. Once I had legs long enough to reach a sewing machine pedal, she taught me how to make pillowcases and aprons.”

That early tutelage inspired a deep passion for wardrobe and costumes in Escobedo. After two years as wardrobe supervisor for Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre Company, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated that she pivot. So Escobedo, who lives on Chicago’s North Side, is now taking part in the City’s Chicago Made workforce development initiative linking residents with film and television productions shooting in the city.

Escobedo received on-the-job training from Local 769 costumers Jennifer Jobst and Angela Verdino as they prepared for an upcoming Netflix feature film to be filmed at Cinespace Chicago Film Studios.

“I’m kind of here to ‘shadow’ as they put the production together, and I can assist as long as I am supervised,” explained Escobedo, adding that she also took Zoom classes for several days that explained the jargon and procedures used by a major production.

“On the job, in film, there is not a lot of time to explain stuff,” she added. “For example, one of the lingo things is, ‘NDB’—non-deductible breakfast—and I had no idea what that meant. Everyone was asking, ‘Nina, did you get your NDB?’ I was like, ‘I don’t know.’”

A Minnesota native, Escobedo moved to Chicago in order to attend the Douglas J. Aveda Institute in Lincoln Park to study cosmetology. She then took what she said was “a left turn” to work in a salon.

“I realized that wasn’t what I wanted to do,” she recalled, and ultimately heard about an opening for the wardrobe supervisor at Lookingglass, where she worked from 2018-2020. The pandemic led to the demise of her job, and Escobedo found herself out of work for the first time.

“It was heartbreaking and hard to navigate at first,” Escobedo said.

Her unemployment was short-lived. A former colleague informed her of an opening in the wardrobe department of the upcoming Apple TV+ thriller series Shining Girls, which debuts in April and stars Elisabeth Moss and Wagner Moura.

“They said, ‘We need someone to start tomorrow, so can you go COVID-test right now?’ I had been sitting on the couch eating junk food, and ran out the door to get tested with my sweatpants on,” Escobedo said.

As her work on Shining Girls was wrapping, she learned of the Chicago Made program. She was unsure of whether to apply, particularly since there was only one opening for wardrobe personnel. But she set her mind on landing the spot: “The pandemic made me think, ‘I’m going to take advantage of every opportunity I can—why not? What do I have to lose?’”

Escobedo values Jobst and Verdino sharing their time and experience. Chicago Made has offered “the training that I wished I had going [into my previous television work],” she said.

“I am so happy to be with them—they’re so patient and they’re so knowledgeable. They are on the job, but they spend time with me and explain all these things.”

Escobedo loves learning the differences between the comparatively drawn-out pace of costuming for the theater and the rapid timing required to do so for television. At the core of both environments though is problem-solving, the aspect of her duties she appreciates the most.

“I love this job because of the community,” she added. “I’ve never been in this job because of the money—it’s my passion. It is the fire in my belly.”

TV + Film Industry Profile

For Chicago Fire stylist Steykine Wills, the main job is about helping to build characters

By Matt Simonette

Chicagoan Steykine Wills, a hair stylist who works full-time for the locally-produced television drama Chicago Fire, sees helping to create characters as a central part of her job.

“Depending on if a character appears disheveled, for example, we have to make them appear that way,” Wills explained. “We have to read the script and make sure that the hair coincides with what the character has going on.”

Wills grew up on Chicago’s South Side, and is a graduate of Myra Bradwell School of Excellence, Simeon Vocational High School, and McCoy Barber College. She had long wanted to use her skills in the film and television industry.

“I had always been interested in doing it—I just didn’t know how to do it,” Wills said. “There were no programs to show you how to get in.”

But a co-worker began working in local film and TV productions and, in 2018, referred Wills to a department head for the HBO series Lovecraft Country.

“From there, I just started building relationships and just started getting callbacks and people asking me to work for them,” she said.

Wills worked steadily on a number of local productions, among them Chicago P.D. and season 4 of Fargo. But then the COVID-19 pandemic hit Chicago, and her work ceased on March 12, 2020.

“‘Two weeks ended up being six months,” she said. “I was off for those six months, just sitting around. But then I started doing online classes, trying to keep up with work, learning different things and doing classes to occupy my time. It was okay, but a little depressing.”

She was brought back to finish up the filming for Fargo, which halted mid-production, and then, in March 2021, landed a full-time position with Chicago Fire.

Most days, Wills is now assigned a different actor to work with. She’ll prepare their hair ahead of shooting, then later go with them to the set and help look after them to keep up with the continuity of their scene over the course of shooting.

“So, for example, if we have someone with long hair, we have to make sure it’s in the same position,” she said. “So we watch the monitor via our iPads and make sure that everything looks the same.”

She said that she was “ecstatic” when she was voted into International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) Local 476.

“I hear a lot of stories about people who were trying to get into their union for years, but it only took me a year,” Will said. “I remember the day. I was riding my bike by the lake and I got a call, and they said, ‘We want to vote you in.’ I was so excited.”

For those looking for a path forward doing hair styling for film and television production, she advises, “Make sure this is something you really want to do. It’s different from being in a salon. You have to dedicate yourself to learning all you can learn… Try to get all of the knowledge that you can before you even get into the business. It’s about a lot more than doing hair—it’s about learning what goes on a set and learning the set lingo. The most important thing is to do your research.”