Information for Health Care Professionals

In many instances health care professionals are the first to intervene after an abusive incident occurs. It is therefore crucial that appropriate intervention strategies be identified and implemented. By accurately assessing the cause of injury, providing necessary medical care, and offering referrals to community resources, health care professionals have the potential to be valuable sources of support. Leaders in the field have identified the following strategies to make interventions by health care professionals more effective.

What You Can Do

- Develop a Standard Intake Form

Create a standardized intake and assessment form to screen every patient for domestic violence.

- Make Resources Available to Patients

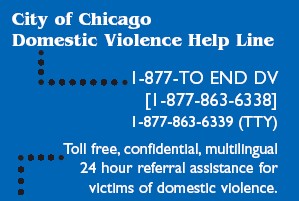

Provide patients with referrals to appropriate community support services. Place resource materials in waiting rooms and restrooms.

- Incorporate Training into Curricula

Support the incorporation of domestic violence and sexual assault training into the standard medical, nursing, and allied health care professional education curricula.

- Support Incorporation of Protocols into Accreditation Process

Support efforts to ensure that domestic violence and sexual assault protocols are addressed through the National Commission for Quality Assurance and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Hospitals.

- Dedicate Continuing Medical Education Hours to Domestic Violence

Ask your state licensing boards and various specialty groups to encourage physicians and nurses to allocate Continuing Medical Education (CME) hours to issues relating to violence against women.

- Encourage Medical Organizations and Societies to Increase Awareness

Collaborate with health care professional organizations and societies in your area to increase medical school and health care professional involvement in addressing violence against women.

- Feature Violence Against Women on Meeting Agendas

Arrange presentations and symposiums on violence against women at annual, regional and local healthcare meetings.

- Highlight Commitment to Violence Against Women Issues

Give awards, citations, and certificates to exceptional organizations and individuals for their continued commitment to addressing violence against women.

- Ensure Employee Assistance Programs are Responsive to Victims of Domestic Violence

Determine whether your health care facility’s employee assistance program (EAP) includes domestic violence services or referrals. If it does not, speak with your human resources director or the appropriate manager about the possibility of expanding the program to address the needs of employees facing violence in their homes. All EAP personnel should receive domestic violence training and have an understanding of the dynamics of domestic violence.

Domestic Violence & Health Care

Researchers at University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and other sites have found that doctors and other health care providers can better their chances of identifying and helping victims of domestic violence by changing the way they ask patients questions.

In a large study recently published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, researchers found a number of communication pitfalls when emergency care providers discussed domestic violence with patients. Some examples: Providers often stumbled over their words, failed to acknowledge a disclosure of abuse or abruptly changed the subject. Occasionally, they screened for abuse in the presence of the woman’s partner.

The study also revealed several best practices for communications. Follow-up questions and open-ended queries, for instance, were found to be helpful in prompting patients to disclose abuse. Patients also tended to open up to providers who showed empathy and concern or those who followed up on non-medical “clues” raised by patients, such when the patient talked about “stress.”

“We found that probing – asking even one more question – was associated with almost three times the rate of patient disclosure of experiences with abuse,” says lead author Karin V. Rhodes, MD, MS, Director of the Division of Health Policy Research in Penn’s Department of Emergency Medicine.

Previous studies showed that patients can be hesitant to disclose their abuse experiences to doctors, but information was scarce about why communication breaks down. To get clues into what happens during these private talks, investigators audiotaped 293 emergency room interactions that included a discussion of domestic violence. Seventy-seven patients disclosed experience with domestic violence during the interviews. Researchers identified several strategies that seemed to prompt more disclosure of abuse, highlighting the need to ask open-ended questions that didn’t use phrases like “victim” or “domestic violence,” which require the woman to view herself as a victim. Re-framed queries such as “Has anyone ever treated you badly or made you do things you don’t want to do?” or “Is there anyone you are afraid of?” tended to elicit disclosures, as did asking empathetic follow-up questions when patients mentioned other psychosocial problems.

The investigators pointed out that while better communication strategies were likely to open the door to meaningful conversations about abuse, patients appreciated being asked about the issue even when the provider asked about abuse in an awkward manner or stumbled over their words. Patients were more likely to rate their satisfaction with the visit as very high if there was any mention of the topic of domestic violence, even if they did not disclose abuse.

The research also revealed problems with provider action once disclosures are made. Less than a quarter of women who revealed abuse were referred to legal or counseling services, and providers generally failed to document domestic violence in the medical record – something that can be helpful if an abused woman ultimately files criminal charges against her partner or seeks protection in civil court. These lapses occurred despite annual domestic violence education programs in each department studied and each provider’s awareness that they were being taped.

Researchers from the Indiana School of Medicine, the University of Chicago and the University of Toronto also participated in the study. Funding was provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institute of Mental Health.

(Source: Newswise Medical News)

Supporting Information Facts

Department:

People We Serve:

- Businesses & Professionals

- Caregivers

- Health Professionals

- Non-Profit Organizations

- Social Service Providers